The Metaphysical poetry

Definition of Metaphysical Poetry.

The word ‘Metaphysical Poetry’ is a philosophical concept used in literature where poets portray the things/ideas that are beyond the depiction of physical existence. Etymologically, there is a combination of two words ‘meta’ and ‘physical in word “metaphysical”.’ The first word “Meta” means beyond. So metaphysical means beyond physical, beyond the normal and ordinary. The meanings are clear here that it deals with the objects/ideas that are beyond the existence of this physical world. Let us look at the origin of word metaphysical poetry in more detail.

Origin of the Word Metaphysical Poetry

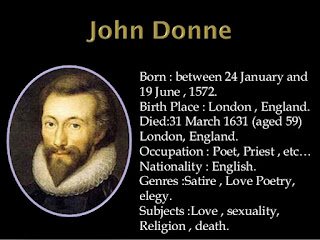

In the book “Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets (1179-1781)”, the author Samuel Johnson made the first use of the word Metaphysical Poetry. He used the term Metaphysical poets to define a loose group of the poets of 17th century. The group was not formal and most of the poets put in this category did not know or read each other’s writings. This group’s most prominent poets include John Donne, Andrew Marvell, Abraham Cowley, George Herbert, Henry Vaughan, Thomas Traherne, Richard Crashaw, etc. He noted in his writing that all of these poets had the same style of wit and conceit in their poetry.

Characteristics of Metaphysical poetry

Metaphysical poetry talks about deep things. It talks about soul, love, religion, reality etc. You can never be sure about what is coming your way while reading a metaphysical poem. There can be unusual philosophies and comparisons that will make you think and ponder.

The most important characteristics of metaphysical poetry is “undissociated sensibility” (the combination of feeling and thoughts).

Even though it talks about serious stuff, it talks about it in a humorous way. The tone is sometimes light. It can be harsh sometimes too. The purpose is to present a new idea and make the reader think.

Another characteristic of such poetry is that it is unclear. Because it provides such complicated themes, the idea of metaphysical poems is somewhat not definite. It is different for every person. It depends on the perception and experiences of the reader. Every person will take something different out of the same poem based on their beliefs and understanding.

Metaphysical poetry is also short. It uses brief words and conveys a lot of ideas in just a small number of words. There are many maxims in this type of poetry too. John Donne introduced sayings into metaphysical poetry.

The unusual comparison of things in poetry is one of its unique and most interesting characteristics. All the metaphysical have ability for unusual witty comparison , juxtaposition, and imagery. These unusual comparison are metaphysical conceits. As Donne in Twicknam Garden uses expression “spider love” that is contrary to the expectations of the readers. In the same poem, Donne also compares a lovers tears to wine of love that is unusual use of juxtaposition. Conceit compares very dissimilar things. For example bright smoke, calling lovers as two points of compass, taking soul as dew drop, etc.

The metaphysical poetry is brain-sprung, not heart-felt. It is intellectual and witty.

According to Grierson, the two chief characteristics of metaphysical poetry are paradoxical ratiocination and passionate feelings. As Donne opens his poem “The indifferent” with a line with a paradoxical comment. “I can love both fair and brown”

Other unique feature of this poetry is Platonic Love. The word is taken after Plato. Platonic love is a non-romantic love. There is no lust or need of physical contact. It is spiritual love and is mostly for God.

Another feature of the metaphysical poetry is its fantastic lyrics style. As A. C. Word said: “The metaphysical style is a combination of two elements, the fantastic form and style, and the incongruous in matter manner”. The versification of the metaphysical poetry is also coarse and jerky like its diction. The main intention of the metaphysical was to startle the readers. They deliberately avoided conventional poetic style to bring something new to the readers. Their style was not conventional and the versification contrast with much of the Elizabethan writers.

It arouses some extreme level of thoughts and feelings in the readers by asking life-altering questions.

Metaphysical Poems

Death (John Donne)

The Flea (John Donne)

The Sun Rising (John Donne)

Ecstasy (John Donne)

The Collar (George Herbert)

To his Coy Mistress (Andrew Marvell)

The First Poem in metaphysical poetry

Death, be not Proud ( Holy Sonnet 10) by John Donne

‘Death, be not Proud’ by John Donne is one of the poet’s best poems about death. It tells the listener not to fear Death as he keeps morally corrupt company and only leads to heaven.

'Death Be Not Proud' is a sonnet written by the English author John Donne (1572-1631). Donne initially wrote poems based on romance, but moved into more religious themes as his career matured. In his later life, he converted from Catholicism to Anglicanism, the official Church of England. His later poems reflect his deep religious faith and his life as an ordained priest and dean of St. Paul's Cathedral in London. 'Death Be Not Proud' is a piece showing the religious undertones in Donne's poetry.

Summary of the Poem

‘Death Be Not Proud” is one of the nineteen Holy Sonnets written by the great metaphysical poet John Donne. As a typical product of Renaissance, Donne wrote a kind of love and religious poetry that shocked its readers into attention with its wit, conceits, far fetched imagery, erudition complexity, colloquial and dramatic styles. Donne’s poetry exemplifies the rare synthesis of reason and passion – a unique quality which is termed as the “Unified Sensibility.”

This poem forcefully demolishes the popular conception of death as a powerful tyrant. The poet presents an unconventional view of death. By addressing the poem to death, Donne says that Death should not feel proud of itself. Death is neither frightening nor powerful although some people have called it so. It has no power over the soul which is immortal. The poet explains his idea through the examples of rest and sleep. He says that rest and sleep are only the pictures of death. We derive pleasure from rest and sleep. So death itself should provide much more pleasure, which is the real thing. Secondly our best men get death very soon. Their bones get rest and their soul gets freedom. Hence death is not frightening thing.

Now the poet blasts the popular belief that death is all powerful. Death, in fact is a captive, a slave to the power of fate, chance, cruel kings and bad men. It lives in the bad company of poison, war and sickness. Opium and other narcotics are as effective as death in inducing us to sleep. They, actually, make us sleep better. Death cannot operate at its own level. So death should not feel proud of its powers.

In the end, the poet once again says that death is a kind of sleep, after which the soul will wake up to live forever and becomes immortal. Then death has no power over us. In other words the soul conquers death; it is the death which itself dies. Thus Donne degrades death and declares happily the impotence of death. It is, in no way, powerful and dreadful. So we should not fear death as it has no power over our souls.

The Flea Summary

The speaker tells his beloved to look at the flea before them and to note “how little” is that thing that she denies him. For the flea, he says, has sucked first his blood, then her blood, so that now, inside the flea, they are mingled; and that mingling cannot be called “sin, or shame, or loss of maidenhead.” The flea has joined them together in a way that, “alas, is more than we would do.”As his beloved moves to kill the flea, the speaker stays her hand, asking her to spare the three lives in the flea: his life, her life, and the flea’s own life. In the flea, he says, where their blood is mingled, they are almost married—no, more than married—and the flea is their marriage bed and marriage temple mixed into one. Though their parents grudge their romance and though she will not make love to him, they are nevertheless united and cloistered in the living walls of the flea. She is apt to kill him, he says, but he asks that she not kill herself by killing the flea that contains her blood; he says that to kill the flea would be sacrilege, “three sins in killing three.”

“Cruel and sudden,” the speaker calls his lover, who has now killed the flea, “purpling” her fingernail with the “blood of innocence.” The speaker asks his lover what the flea’s sin was, other than having sucked from each of them a drop of blood. He says that his lover replies that neither of them is less noble for having killed the flea. It is true, he says, and it is this very fact that proves that her fears are false: If she were to sleep with him (“yield to me”), she would lose no more honor than she lost when she killed the flea.

The Sun Rising Summary

Lying in bed with his lover, the speaker chides the rising sun, calling it a “busy old fool,” and asking why it must bother them through windows and curtains. Love is not subject to season or to time, he says, and he admonishes the sun—the “Saucy pedantic wretch”—to go and bother late schoolboys and sour apprentices, to tell the court-huntsmen that the King will ride, and to call the country ants to their harvesting.

Why should the sun think that his beams are strong? The speaker says that he could eclipse them simply by closing his eyes, except that he does not want to lose sight of his beloved for even an instant. He asks the sun—if the sun’s eyes have not been blinded by his lover’s eyes—to tell him by late tomorrow whether the treasures of India are in the same place they occupied yesterday or if they are now in bed with the speaker. He says that if the sun asks about the kings he shined on yesterday, he will learn that they all lie in bed with the speaker.

The speaker explains this claim by saying that his beloved is like every country in the world, and he is like every king; nothing else is real. Princes simply play at having countries; compared to what he has, all honor is mimicry and all wealth is alchemy. The sun, the speaker says, is half as happy as he and his lover are, for the fact that the world is contracted into their bed makes the sun’s job much easier—in its old age, it desires ease, and now all it has to do is shine on their bed and it shines on the whole world. “This bed thy Centre is,” the speaker tells the sun, “these walls, thy sphere.”

Ecstasy Summary

Where, like a pillow on a bed

A pregnant bank swell’d up to rest

The violet’s reclining head,

Sat we two, one another’s best.

Our hands were firmly cemented

With a fast balm, which thence did spring;

Our eye-beams twisted, and did thread

Our eyes upon one double string;

So to’intergraft our hands, as yet

Was all the means to make us one,

And pictures in our eyes to get

Was all our propagation.

As ‘twixt two equal armies fate

Suspends uncertain victory,

Our souls (which to advance their state

Were gone out) hung ‘twixt her and me.

And whilst our souls negotiate there,

We like sepulchral statues lay;

All day, the same our postures were,

And we said nothing, all the day.

If any, so by love refin’d

That he soul’s language understood,

And by good love were grown all mind,

Within convenient distance stood,

He (though he knew not which soul spake,

Because both meant, both spake the same)

Might thence a new concoction take

And part far purer than he came.

This ecstasy doth unperplex,

We said, and tell us what we love;

We see by this it was not sex,

We see we saw not what did move;

But as all several souls contain

Mixture of things, they know not what,

Love these mix’d souls doth mix again

And makes both one, each this and that.

A single violet transplant,

The strength, the colour, and the size,

(All which before was poor and scant)

Redoubles still, and multiplies.

When love with one another so

Interinanimates two souls,

That abler soul, which thence doth flow,

Defects of loneliness controls.

We then, who are this new soul, know

Of what we are compos’d and made,

For th’ atomies of which we grow

Are souls, whom no change can invade.

But oh alas, so long, so far,

Our bodies why do we forbear?

They 'are ours, though they 'are not we; we are

The intelligences, they the spheres

We, two lovers, each thinking of the other as the best person in the world, sat on the river-bank which was raised high like a pillow to enable the reclining heads of violet flowers to rest on it. Our hands were firmly grasped and from them a strong perfume emanated. Our eyes met and reflected the image of each other. It appeared as if our eyes were strung together on a double thread. Our hands were firmly clasped together and this was the means of bringing us close to each other. Our eyes reflected our images and this was the only fusion of our love.

Just as when two equally powerful enemies fight each other while fate holds the victory in a state of balance, undecided which way to turn the scale, in the same way, our souls, which had left our bodies to sublimate to a state of bliss, hung between the two of us uncertain of their future. While our souls, communicated with each other in this situation, we lay quiet and motionless like statues built over the monument of the dead. All thought the day our bodies continued to remain in the same position without movement or speech.

If any stranger, whose soul had been purified by a similar process had stood beside our souls, and had been capable of understanding the language of the souls his purified mind would have forgotten the existence of the body and enlightened and sharpened the faculties of his mind, such a soul may not have understood the conversation of our souls because both our souls meant and spoke the same thing, but that soul might have undergone a fresh process of purification and felt more refined than before.

Our souls have reached a state of ecstasy which revealed to us what we did not know earlier. We realized that love was not sex experience. We discovered the first time that love really is a matter of the soul and not of the body. Souls are made of various elements of which we have no knowledge. It is love which brings together two souls and makes them one, though, in reality, the two have senate existence.

When a violet plant is transplanted (removed from one place and replanted in a better soil) it shows a marked improvement in its colour, size and strength. After transplantation it almost doubles itself and also grows more rapidly. In a similar manner when love brings two souls together it imparts to them a great zeal and life. The stronger (or noble soul) supplements (or removes) the deficiencies of the lesser soul. Love also removes the feeling of loneliness felt by single souls.

As a result of the union of two souls, so to say, a new soul comes into being. This new soul knows of what elements the two souls are composed. It makes us realize that the substances of which we are made are not subject to any change.

Alas, we have so far and so long ignored our bodies. The bodies are ours, but we are distinct from the bodies. We are souls; we are of spiritual substance; we are like heavenly planets while our bodies are the spheres in which we move.

We are thankful to our bodies, because they brought us together in the first instance. Our bodies surrendered their sense in order to enable our love to be spiritual. Our bodies are not impure matter, but they are like an alloy (an alloy when mixed with gold makes it tougher and brighter). The body is useful agent for holy love.

The influence of heavenly bodies on man comes through the air. So when a soul wishes to love another soul, it can contact it through the medium of the body. Hence a union of souls may need the contact of bodies as the first step.

Just as the blood which is an important constituent of our bodies labours to produce the essence (the semen) which helps in uniting two bodies, in the same way a spiritual love produces a kind of ecstasy which binds the two souls together. This subtle knot of love may not be fully understood.

Just as blood produces elements which brings about the union of sense and soul which constitute a man, in the same way the lover’s soul leaves some linking elements like the sense and the bodily faculties to express their love. The sense and faculty of the body come to the aid of the soul, which is like a prisoner. Just as a prince who is imprisoned cannot gain freedom unless somebody comes to his aid, in the same way the senses of the body go to the aid of the lover’s soul and secure freedom for it.

We must now turn to our bodies so that weak men may have a test of high love. Love sublimates the soul but it is through the medium of the body that love is first experienced. The body is as important as the soul in the matter of love.

If some lover like us has heard this discourse (made by two souls with one experience) let him look carefully at us. After our pure love when we go back to our bodies he will find no change in us because we shall not revert to physical self again.

The collar summary

In the first sixteen lines of the poem, the speaker (or “the heart”) states that he’s uninterested in the present state of affairs and plans to hunt out his freedom. He laments that he’s “in the suit,” during a lowly position, which he has not reaped greater rewards. As these lines progress, we learn that the speaker has undergone a period of pining and sadness, resulting in his present anger.

In lines 17-26, another inner voice interjects, “not so, my heart,” reminding the primary speaker that there’s an end to sadness in view. If only the speaker will “leave [his] cold dispute” and stop his rebellion, he is going to be ready to open his eyes and see the reality.

In lines 27-32, the desire reappears, commanding the opposite speaker “away!” and restating his commitment to going abroad. within the final four lines of the poem, the irregular vers libre gives thanks to an ABAB rhyme scheme. The second inner voice reveals that, even within the midst of raving, he heard someone calling “Child” and replied “My Lord.” this means a return to God after a period of rebellion.

The metaphysical poetry a last poem

To his Coy Mistress summary:

Andrew Marvell was a metaphysical poet writing in the Interregnum period. He sat in the House of Commons between 1659 and 1678, worked with John Milton, and wrote both satirical pieces and love poetry.

“To his Coy Mistress” is a poem in carpe diem tradition. It is a plea from a lover to his beloved to forget her coyness and engage in the pleasures of love. The poem begins abruptly with these words, “Had we but world enough and time”, he continues, “this coyness lady were no crime”. The reason for such a plea is being established using a series of hyperbolic comparisons. If there is enough time and space, then, the coyness that the lady shows would have been appreciated. Then, the poet would have sat by the river Humber in England and complained about the coyness of the lady who would be sitting on the banks of the river Ganges on the other side of the world. He would begin to love her ten years before the biblical flood and, she, if she wants, could refuse until the comparison of the Jews i.e. the end of time itself. Marvell argues that his vegetable love could slowly grow greater than the empires. If he had time, he would devote a hundred years to praise her eyes, two hundred two each breast, and thirty thousand to the rest of her. He would spend at least an age to admire every part and the last age might praise her heart.

In the second stanza, the poet portrays the picture of a man who lives with the fear of death. The awareness of times winged chariot hurrying near frightens us all. In our destined tombs, the loved one’s beauty will slowly but surely turn to dust. The virginity that she coyly preserves may be taken up by worms. He calls the grave, ‘a fine and private place’ though not a place of ‘embrace’. In the last stanza, Marvell reaches the conclusion that, as they are young and beautiful, rather than languishing as prisoners of time, ‘let us sport while we may’. He suggests that the strength of the man and the sweetness of the woman when united may 'roll-up’ into one ball. The violence of sexual art is described through the image ‘tear our pleasures’ which acts as an image of the desperation with which they try to defeat times winged chariot. Finally, with reference to an incident described in bible (when Joshua made sun stand still), he asserts that even time would not be able to cease their love. The poem convinces the readers about the pleasures of physical love with its syllogistic arguments and its unique tone mixing eroticism and wit.

Words:3872